Among the rugged landscape of the North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan), a region renowned more for warriors than pacifists, a man was born whose ideals would astonish even the most scholarly historians. Abdul Ghaffar Khan, better known as Bacha Khan, was born in 1890 in the town of Utmanzai. A giant in terms of stature as well as virtue, he was a visionary leader who would radically alter the Pashtun social and political environment forever.

From Privilege to Purpose

Coming from a wealthy family of landowners, Bacha Khan might have lived a life of ease and quiet. But early exposure to the injustice of the British Raj and the debilitating backwardness of his people awakened something in him. He perceived the shackles of colonialism not merely in political terms, but in the absence of education, the tribal rivalries, and the lack of dignity among the poor.

He started with the most powerful tool he could discover—education. He founded schools and promoted female education, even in the face of intense opposition from traditional tribal circles. He was convinced that without knowledge, no people would ever be free.

The Birth of the Khudai Khidmatgar Movement

In 1929, Bacha Khan started the Khudai Khidmatgar (Servants of God) movement. His volunteers, clad in red uniforms, were famously called the “Red Shirts”. They were unarmed soldiers, but nonviolent resisters—educated in discipline, service to society, and nonviolent resistance. They swore oaths to serve humanity, never take revenge, and struggle against injustice by peaceful means.

This was a radical concept in a part of the world where blood feuds and violence were traditions. To be able to instruct nonviolence to the Pashtuns, who were proud of their warrior traditions, was no easy task. But Bacha Khan achieved it, without force, by example. His integrity, humility, and selflessness commanded a respect that was unparalleled.

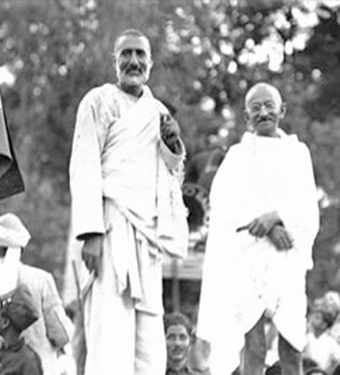

The Bond with Gandhi

Bacha Khan’s philosophy of nonviolence naturally aligned with Mahatma Gandhi. The two met and immediately found a deep kinship. Gandhi saw in Bacha Khan a rare courage: a man preaching peace in a place where peace was often mistaken for weakness. Bacha Khan became one of Gandhi’s most loyal allies, despite being a devout Muslim in a movement often branded as Hindu-dominated.

They were spiritual brothers, both espousing a free and equitable India, not split along religious, caste, or ethnic lines. Bacha Khan’s support for the Indian National Congress against the Muslim League aligned him with the prevailing political trend in Muslim-majority areas.

A Voice Against Partition

Bacha Khan was a strong critic of the Partition of India. He could see that partitioning the subcontinent on the basis of religion would not usher in peace—it would only intensify the wounds of colonialism. He urged people to be united even when communal politics swept the nation.

When Pakistan was formed in 1947, Bacha Khan and his supporters were left politically orphaned. They had fought Partition and were labeled as traitors. Even though they had fought for freedom as hard as anyone else, they were marginalized in the new nation. Bacha Khan’s party, the Frontier Congress, was outlawed. He was repeatedly imprisoned, spending more than 30 years of his life behind bars—many times under the very nation he had fought to free.

Forgotten, But Not Defeated

In the initial decades of Pakistan’s life, Bacha Khan was a dissenting voice. He spoke against military dictatorship, ethnic minority oppression, and erosion of democratic values. Even in his advanced age, his beliefs were unwavering. He believed in Pashtun identity, nonviolence, and democracy and could not be silenced.

Even with the state’s efforts to erase or downplay his legacy, his message spoke to generations. His people continued to promote peace, pluralism, and regional autonomy. His vision was never a vision of separation—it was one of dignity for all.

A Farewell that Defied Borders

Bacha Khan died in 1988, aged 98. His dying wish was a symbolic one—his wish to be buried in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, was to silently protest the political oppression he encountered in Pakistan. His funeral procession was different from any other South Asian funeral ever. Despite an ongoing war raging in Afghanistan, a ceasefire had been agreed on so people across the border and on it were able to witness his funeral.

It was a silent rebellion, even unto death—a reminder that his ideals could not die.

Legacy of Bacha Khan: A Global Torchbearer of Peace

Bacha Khan, often called the “Frontier Gandhi,” is still celebrated all over the world for his strong belief in nonviolence and social justice. His impact can be seen not just in places named after him but also in the arts and literature that honor his legacy.

Back in 2008, director and writer T.C. McLuhan shared Bacha Khan’s story with the world through the documentary The Frontier Gandhi: Badshah Khan, a Torch for Peace. It debuted in New York and won the Best Documentary Film award at the 2009 Middle East International Film Festival, helping spread his message of peace even further.

His ideas around Islamic pacifism and his lifelong efforts have gained him respect well beyond South Asia. Hillary Clinton, former U.S. Secretary of State, spoke about his role in peaceful resistance to American Muslims. He even made it into a U.S. kids’ book, featured alongside well-known figures like Tiger Woods and Yo-Yo Ma.

Many places in South Asia are named after him as well. In his home country of Pakistan, Peshawar’s airport is officially Bacha Khan International Airport, and there’s also Bacha Khan University in Charsadda, where his vision for education and reform is honored.

In India, you can see his legacy in different cities too. Delhi has Khan Market, which is one of the city’s top shopping spots, and Ghaffar Market in Karol Bagh is named for him as well. Over in Mumbai, the seaside road in Worli is called Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan Marg, a constant reminder of his lasting influence.

His life and achievements have inspired many written works. He wrote an autobiography back in 1969, and authors like Eknath Easwaran and Rajmohan Gandhi have dove deep into his story, making sure that this remarkable champion for peace continues to motivate future generations.

Bacha Khan’s legacy is deep but yet not well-recognized in popular South Asian histories. He demonstrated to the world that Islam and nonviolence are not incompatible, and peace and pride can be accommodated along with Pashtun pride. His life defies the stereotypes leveled against his people—of violence, of extremism, of backwardness.

He is still remembered with respect in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and by peace-loving individuals around the globe. Schools, roads, and foundations are named after him. His autobiography “My Life and Struggle” still inspires those who look for justice through nonviolence.

In calling him the “Muslim Gandhi,” many seek to find logic in Bacha Khan’s inspiring story. Perhaps, though, that title, well-intentioned as it is, fails. He wasn’t a clone of Gandhi. He was his own individual—born of mountains, tempered through resistance, and risen through peace.In a time when violence tends to take center stage, Bacha Khan’s strength of silence reminds us that the greatest revolutions start not with a gun, but with a book… and a faith in humanity.