Languages are living histories of human society. They build with empires, flow over trade roads, influence philosophies, and sometimes retreat as new nations come to center stage. The Arabic language is one such language. A premier force once in the world in the sciences, literature, and religion, today it serves a narrower purpose on the world stage. We must trace the path of Arabic from its early beginnings through to the present.

Humble Beginnings in the Arabian Desert

Arabic originated as the language of the Bedouin tribes all over the Arabian Peninsula. It was very poetic and expressive, transmitted orally and rich in metaphors and rhythms. Before the 7th century, Arabic had little influence beyond its geographical context.

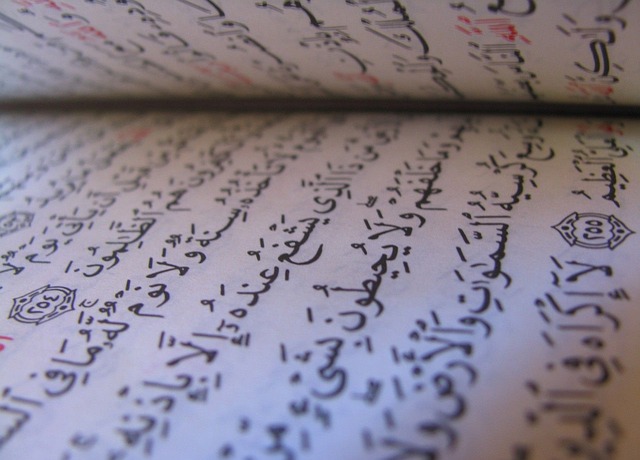

All this changed with the advent of Islam. Since the Quran was revealed in Arabic, the language soon acquired religious significance. It became the holy language of a fast-growing religion and soon started spreading far and wide beyond its homeland.

The Islamic Expansion and the Rise of Arabic

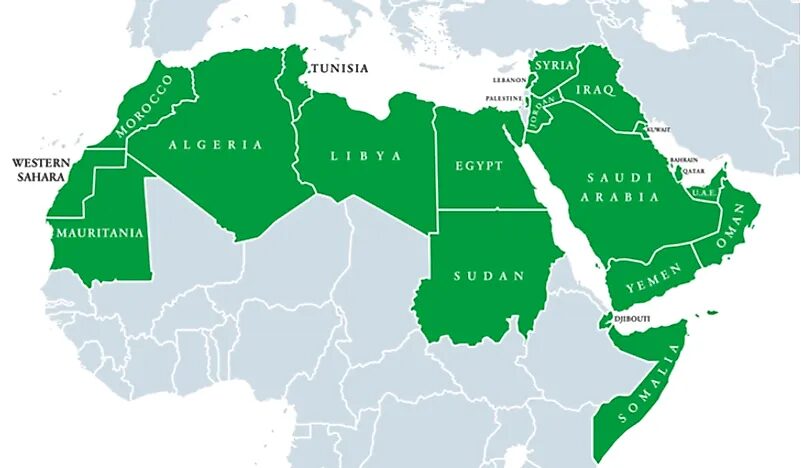

As Islam spread quickly, Arabic came along as both an administrative and religious language. It was used by newly founded Muslim countries in Persia in the east and Spain in the west for governance, education, and legal frameworks.

The language transformed into something more than a tool of communication. It was now a symbol of unity between many different cultures and people. Islam converts, both ethnically and regardless of their ethnicity, used Arabic for praying, studying, and living out in public life. This ensured its place as a common language throughout a massive and diverse empire.

The Golden Age of Knowledge and Culture

By the 8th century, during the Abbasid Caliphate, Arabic was at its intellectual peak. Baghdad, the caliphate’s capital city, was a magnet for scholars, scientists, and philosophers from all over the known world.

The city’s House of Wisdom was a hub of translation and scholarship. Works from Greek, Persian, Indian, and Syriac sources were translated into Arabic, making available to scholars the centuries of accumulated knowledge. But they didn’t just translate—they created. Arabic scientists such as Al-Khwarizmi created algebra, Ibn Sina built on medicine, and Alhazen studied optics. Philosophers such as Al-Farabi and Averroes engaged with Greek philosophy and re-interpreted it in an Islamic sense.

Arabic at this period in time emerged as the language of science, philosophy, and art worldwide. It was used as the platform by which the world thought, discussed, and discovered.

The Beginning of Decline

As with every empire, internal fissures and pressure from the outside caused the political cohesion which had allowed Arabic to dominate to weaken. The huge Islamic empire broke into smaller states. In the east, Persian re-emerged as the language of literature and scholarship. In the west, local languages and dialects started gaining ground.

The 1258 Mongol sack of Baghdad was a cataclysmic event. It was the symbolic and actual dissolution of the Abbasid Caliphate. Baghdad, center of intellectual life, was destroyed. The destruction of institutions such as the House of Wisdom speeded the disappearance of Arabic as the language of science and scholarship.

Colonialism in the modern era gave a crushing blow to Arabic’s international reputation. European colonial powers took over control of most of the Arab world from the 19th century onwards. French was imposed in North and West Africa, while English emerged victorious over Egypt, the Gulf, and the Levant.

These colonial languages were institutionalized in government systems, schools, and legal systems. Post-independence, they remained predominant in higher education and official contexts. Arabic became reserved for religious contexts or common usage.

This bilingual heritage continues to this day. In most Arab nations, mathematics and science are taught in English or French. Arabic-published research is underrepresented in international databases. A feeling of linguistic dependency, based on the colonial era, still exists.

The Complex Present of Arabic

Arabic is still a world language. It is spoken by over 400 million and one of the official languages of the United Nations. It remains the language of religion, culture, and identity for millions.

But it has a major internal problem. Perhaps the most distinctive is diglossia—the clear dichotomy between Modern Standard Arabic (employed in the media, books, and formal texts) and the local dialects used in everyday communication. This can lead to a linguistic divide that influences education, the media, and national cohesion.

Additionally, the global primacy of English in science, technology, and world business teaches Arabic’s effective use in international affairs even further. It is common to find young Arabs proficient in foreign languages but disconnected from formal Arabic, perceiving it as formal, obsolete, or cumbersome.

Efforts Toward Revival and Modernization

In spite of these setbacks, there is a renewed drive to revive Arabic. Governments and institutions throughout the Arab world are putting money into Arabic-language schooling, web content, and scientific jargon.

Such nations as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia are implementing programs aimed at the popularization of Arabic in technology and education.Digital platforms and book publishers are offering more Arabic-content material for the youth. Channels of media are marketing Arabic shows and fostering pride in language.

There is a new cultural interest in Arabic poetry, narrative, and calligraphy—linking contemporary Arabs with their literary tradition while seeking out relevance today.

Arabic has a complicated and storied past. It has been spoken by empires, written in by many of the world’s most notable intellectuals, and was a beacon of faith to well over one billion Muslims.

Although it may no longer be at the center of global attention in science and global diplomacy, its narrative is far from over. At a time when the world is more focused on identity, roots, and cultural revival, Arabic has a fertile ground to construct its narrative on. The test is to reconcile tradition with modernity. In order for Arabic to survive in the 21st century, it has to learn how to connect with science, technology, and world culture without sacrificing its soul. If that balance can be achieved, then Arabic can once again discover a new voice in determining the future of the world.