Imagine a gift that looks beautiful and innocent. It’s a stunning wooden plaque, shiny and polished, showcasing the Great Seal of the United States. This plaque was given by a group of grateful kids, a thoughtful gesture from one superpower to another during a delicate time of peace.

But what if that gift was hiding one of the smartest spy devices ever created?

Welcome to the story of the Great Seal Bug, a Cold War enigma that caught American intelligence off guard. This was a bug that didn’t buzz or blink and didn’t need batteries. It was a quiet listener blending right into the background, just behind the desk of the U.S. ambassador.

A Gift from Russia, with Love?

Back in 1945, right after World War II wrapped up, the U.S. and the Soviet Union were on shaky ground but still considered allies. To celebrate this uneasy friendship, a group of Soviet schoolchildren gifted a handsome wooden plaque to W. Averell Harriman, the U.S. Ambassador to the USSR. It stood about two feet tall and was carved with the Great Seal—a bald eagle holding arrows and an olive branch.

Harriman was touched by this gesture and hung the plaque on the wall of his residence in Moscow, right behind where he worked. It stayed there for a whole seven years, and during that time, many secrets whispered in that room were no longer safe.

Not Your Average Bug

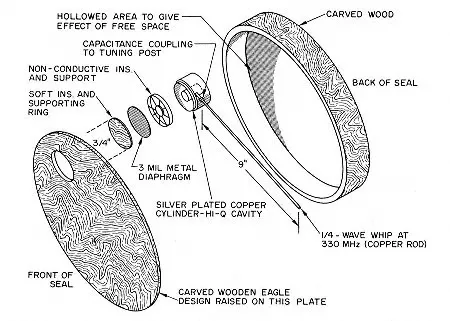

This wasn’t just any old spy microphone. What the Soviets had secretly planted was something far more ingenious. It had no batteries, no wires, and no transmitter in the usual way. American spies hadn’t even thought up such a device until then.

Inside the plaque was a tiny listening gadget that came to be known as “The Thing.” This clever device was created by Leon Theremin, the same guy who invented that eerie-sounding electronic musical instrument that shares his name. But this was no music; this was high-stakes espionage.

How “The Thing” Worked

So how did it all work?

“The Thing” was a passive cavity resonator. It only kicked in when it picked up a special radio frequency from a Soviet van parked nearby.

When the Soviets sent a radio signal at the plaque, the hidden antenna inside would resonate. If someone was talking, sound waves would make a tiny diaphragm in the device vibrate. These vibrations would tweak the radio waves that bounced back to the Soviets’ listening posts.

When the signal stopped, so did the bug. No noise. No trace of power. It was like a ghost.

The Discovery

For seven years, American diplomats chatted privately while the Soviets snuck a listen. It wasn’t until 1952 during a regular security check of the embassy that British and American techs noticed some odd radio signals when a specific frequency was sent out.

They figured out the source was that Great Seal plaque. When they opened it up, they found the bizarre-looking device—something totally alien to Western intelligence.

The Americans couldn’t believe how advanced it was. This thing was decades ahead of what they thought was possible.

From Moscow to the UN

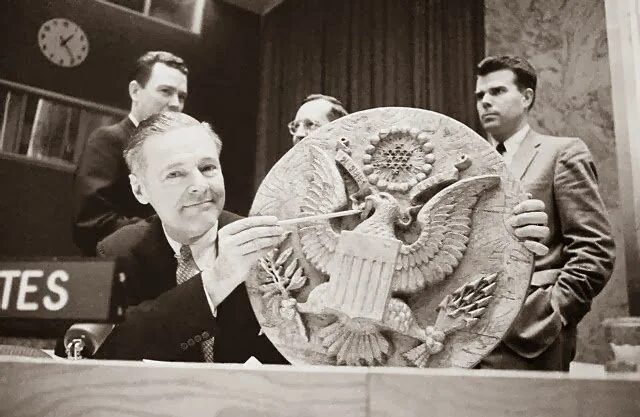

In 1960, the Americans finally spilled the beans about the Great Seal Bug to the world.

Why now? Well, the Soviets had just shot down an American U-2 spy plane and were pointing fingers at the U.S. for spying. So, Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge took to the United Nations with a real-life response: the actual bug taken from the Great Seal plaque.

He raised it for everyone to see, a chilling reminder that both sides played dirty—just that the Soviets pulled it off brilliantly.

A Masterclass in Spycraft

What made the Great Seal Bug so creepy wasn’t just how it was made—it was how stealthy it was.

- It didn’t send out signals unless it was activated.

- It was hidden in a decorative object that nobody would think twice about.

- It ran on RF energy, a tech concept that wouldn’t hit the West until years later.

- It stayed unnoticed for seven years in a government building.

Today, “The Thing” is looked at as one of the most advanced passive listening devices ever made. It changed the game for modern RF surveillance and kicked off a new wave of counterintelligence tech.

The Legacy

The Great Seal Bug wasn’t just a neat trick—it was a wake-up call. It showed Western intelligence that their rivals could pull off some seriously impressive tech work.

It also marked a change in the Cold War—from outright battles to sneaky espionage. Instead of tanks and missiles, it became all about microphones and clever devices.

That plaque, which is now showcased in museums, stands as a symbol of Cold War cunning—a silent witness to the art of spying.

Final Thoughts

The Great Seal Bug reminds us that in the world of spies, often what’s the most dangerous is what you can’t see.

It was a feat of engineering, a master deception, and a lesson in not trusting appearances—even when it’s a gift from kids.

Next time you hang a decorative plaque on your wall, it might be worth giving it a second glance. Just in case.